Wizard Grenade

Published 4 Jan 2021

My first real programming project, used to learn object oriented programming. Wizard Grenade is complete a video game based on Worms2 where opposing teams of Wizards launch magical projectiles at each other.

Wizard Grenade was born after challenging myself to recreate Worms2, one of my childhood favourite PC games, using pixel art I had made for another project. The game is developed almost entirely from scratch, composed of 65 classes, running on Monogame, which runs the game-loop and draws the sprite-batch to the screen. The aim was to develop a playable game with a basic physics engine, and destructible terrain, before my arbitrary three-month deadline. I finished on time but couldn’t help spending an extra week tweaking aesthetics and scoring a simple theme tune. This project taught me a lot of important lessons about software architecture and object-oriented programming. This page discusses some of these lessons and highlights different aspects of the application.

Getting this game containerised and playable via the browser is on my ever growing todo list!

Contents

screenshot of a battle in Wizard Grenade

PhysicsPhysics

The physics are what really spawned this project - after replaying Worms2 for the first time in at least a decade, the simple act of aiming and timing tricky grenade throws was so satisfying that I wanted to recreate it. Upon achieving this, armed with a modest level of new programming knowledge I thought, “I’ll just make the whole game, it can’t be that much work!” … that thought did not last long, but at least it didn’t deter me. In truth, the physics only needs to approximate a simple mechanical model. For this I created a class called GameObject, which is included in every object that is acted upon by gravity and collides with the map, such as the fireballs or the wizards.

Fig1. Collision points about different GameObjects

GameObject class

As each

GameObjectis drawn to the screen, it inherits from theSpriteclass. In hindsightGameObjectcould contain aSpriterather than inherit to reduce coupling between the two.The

GameObjectconstructor takes another class calledGameObjectParameters, which includes the essential physical properties: mass, dampingFactor and numberOfCollisionPoints, as well as the parameters required to load the Sprite. The GameObject and Sprite class constructors are overloaded to take animation frames for animated sprites.

public class GameObjectParameters

{

public bool CanRotate { get; set; }

public readonly string fileName;

public readonly int framesH;

public readonly int framesV;

public readonly int numberOfCollisionPoints;

public readonly float mass;

public readonly float dampingFactor;

// constructors

}The GameObject constructor initialises another class called Polygon with the number of collision points. If 0 is passed, then the corners of the Sprite are picked (like the arrow in Fig. 1), else a circle is drawn in points about the centre of the Sprite (Wizard and Fireball).

In essence, GameObject makes the position of a Sprite responsive to gravity, and collisions with the map. We control this by modulating the object’s 2-dimensional velocity on each game loop, which then acts on the current position. Another class, Space2D contains properties of position, velocity and rotation.

Each frame, or loop of the game code, a GameObject velocity is influenced by acceleration due to gravity in the direction ‘+y’, which is relative to the object’s mass. The (x, y) vector acceleration due to gravity each frame is then: (0, GRAVITY * mass), which is simply added to the current velocity. However, before updating the object’s position we need to check if the new position would make any collision points overlap with the map. To do this, I gave each GameObject a separate instance of Space2D for “real space” and “potential space”.

The Polygon contains the collision points relative to the object at position (0, 0), and a set of transformed collision points; this only contains half of the points as we only need to check collisions in the direction we are travelling. The transformed points are calculated each frame from the current position and velocity. In Fig. 2 the Wizard is falling straight down, so the collision points are centred around (0, +y).

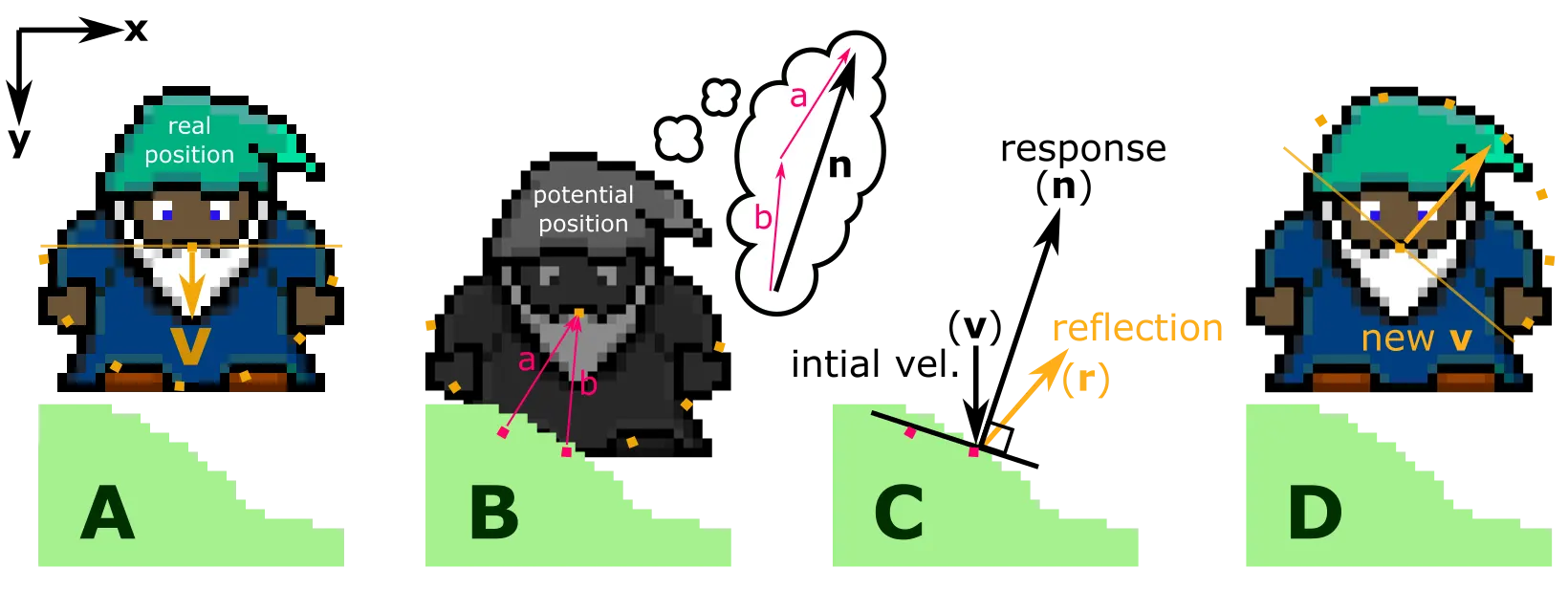

Now, looking at Fig. 2A we have a GameObject falling with an initial velocity (0, +y). At the beginning of the loop the gravity is applied to the initial velocity, and the potential position is calculated. Fig. 2B shows that two of the collision points in potential space are overlapping with the map.

The Map is loaded in at the beginning of the game as a 2D ‘bool’ array for each pixel: true for colour and false for transparent. The x and y floating point values for a given collision point are cast as integers and checked against the 2D map array. If the result at that array index is true then the point is “colliding”.

As in Fig. 2B we draw vectors from all colliding points to the object centre, and sum them which creates a response vector; this is perpendicular to a line which approximates the colliding surface of the map.

From this we use the dot-product of initial velocity (v) and normalised response vector (n) to get the reflection vector (r), which becomes the new velocity: r = v - 2( v . n )n. By normalising (n), the magnitude of (r) depends only on the magnitude of (v).

The reflection or new velocity is multiplied by a dampingFactor to simulate friction; each GameObject has a different dampingFactor to allow us to control how bouncy an object is.

Finally the new velocity is added to the previous position, and the object is drawn at it’s new position. These ideas for pixel level collision resolution were inspired by an excellent YouTube channel javidx9.

Some objects rotate to the direction they are travelling, in which case the rotation angle is calculated from the new velocity and the object is drawn at this angle. The Wizard however faces downwards, so all Wizards are drawn at the same angle regardless of velocity.

GameObjects can have velocities imparted upon them by an explosion or being hit by an arrow. This is all taken into account each frame of the game loop and factors into the final velocity and position, creating a sufficient approximation of classical mechanics.

Architecture

Architecture

You might wonder why this project is “WizardGrenade2” on GitHub - For WG1 I did what all green programmers do and got carried away trying to make things work (i.e make fireballs bounce around) and didn’t think about the structure of my program. I made the rookie error of having my GameObject class handle everything from physics to drawing to collisions; I essentially packed too much functionality into one class which resulted in a very tightly-coupled application. So I started from scratch with more of a plan. Below is a UML diagram, approximating the architecture of WizardGrenade2. The classes in red are Singletons which I know can be a touchy subject! I decided to use them for classes which would only have a single instance required (such as the StateMachine) and needed to be referenced from multiple different areas of the application - I think I could improve this in the future but this was how I chose to go about it at the time. The free account on LucidChart restricts the number of objects so it isn’t complete but gives the idea, as UML diagrams should. The basic structure is as follows:

UML diagram for Wizard Grenade codebase

WGGame is the main game class. This handles the game loop logic, determines whether we are in the menu, running the game, or if the game is paused. It also contains the CameraManager which determines the origin matrix (i.e. drawing UI, menus) and the transform matrix (i.e. in game)

The GameSetup is a menu where the game options and map are chosen - once selected a small GameOptions class is injected as a constructor to GameScreen along with the ContentManager.

The GameScreen passes on the GameOptions to the BattleManager which loads the respective number of Teams and sets the number of Wizards per team; each Team calculates their total health and feeds this back to the GameScreen which primes the UserInterface with the team HealthBars and the round time

Teams handles the initial placement of the Wizards, and after that polls the StateMachine for the active GameState and determines which Team and Wizard are active.

Each Team has a different Sprite so this is where each Wizard is drawn and where the collective health is tallied. The movement method is only called for the active Wizard of the active Team.

Improving on my last design, the Wizard class handles movement, damage and animation states but has a GameObject (see below). The Wizard also contains an Entity which has health, a “Damage()” method and checks if the Wizard is dead or not.

The GameObject class handles the physics (see Physics) and draws the Sprite at the correct position. In hindsight I could have decoupled this further by containing the Sprite within GameObject rather than inheriting from it.

Another improvement on the first design was having the WeaponManager handle all the weapons and simply draw them at the position of the active Wizard. The WeaponManager is updated by the BattleManager and takes the active wizard position in it’s Update() method.

The WeaponManager class is one of the dreaded Singletons which acts as a conduit between the Wizards and the Weapons. The WeaponManager is Lazy Initialised so it is only called once the teams are loaded; a list containing all Wizards is collected by Teams and passed to the WeaponManager. Then when a Weapon explodes near a Wizard the WeaponManager can call AddVelocity() on the Wizard (or any other GameOjbect) and make them react to the explosion

The explosion imparts a velocity value as function of distance from the explosion, which causes variable amounts of damage depending on how close the Wizard was to the explosion

The way each Weapon interacts with Wizards is different, hence they contain virtual methods to be overriden by the specific weapon class. I intend to prepare another section on how these weapons work in the future.

Terrain

Destructable Terrain

The next aspect of Worms2 to figure out was how to make the terrain destructible, and react to the weapon explosions but remain collidable. This actually proved fairly simple because the collision physics already takes place at the pixel level. So really this is a discussion of how the Map class works. Now, the Map class is one of the dreaded singletons that I used in the design of this game, because I wanted weapon objects to be able to call the DeformLevel() method without each object requiring a reference to the Map class. The Map class is also referenced by the CollisionManager, which all GameObjects need access to, so this is a singleton too. In my first iteration of the game, I didn’t use any singletons but I did have to pass a lot of information up and down through a complex heirarchy of classes, which felt rather messy and coupled everything togther too tightly. I understand that a singleton in essence does the same thing, but I have more experience now. Nonetheless, I will break down the main sections of the Map class and explain how we get destructible terrain.

A firebomb blowing a chunk out of the map!

Loading the Data

The Map class is Lazy initialised, which means it doesn’t get instantiated until it is first called in the code. This happens after the user has selected the Map which they want to battle on. I have each file named “map” followed by a number, so the number is what is selected upon loading. The LoadContent function takes the file name and a bool called “isCollidable”, and attempts to load the image into a “Texture2D” called _mapTexture. I used a try, catch block for some defensive programming; If the file name does not correspond to an accessible file it will load a deafult file. First the data for each pixel is read contigously from the map Texture2D (“_mapTexture”) into a uint[] “_mapPixelColourData”, starting at index 0 and running through the whole map. The LoadPixelCollisionData() method then reads this into a 2D bool array, which corresponds to the rows and columns from the contiguous array of colour data. Wherever there is a transparent pixel in the .png file, the colour data is recoreded as ‘0’. Because each element of the bool[,] is initialised to false, we check if the colour value is != 0, and if so set it to true.

public sealed class Map

{

private Map() {}

private static readonly Lazy<Map> lazyMap = new Lazy<Map>(() => new Map());

public static Map Instance { get => lazyMap.Value; }

public bool[,] MapPixelCollisionData { get; private set; }

private uint[] _mapPixelColourData;

private CollisionManager _collisionManager;

private Texture2D _mapTexture;

private Vector2 _mapPosition = Vector2.Zero;

private readonly string _defaultFileName = @"Maps/Map2";

public void LoadContent(ContentManager contentManager,

string fileName, bool isCollidable)

{

try { _mapTexture = contentManager.Load<Texture2D>(fileName); }

catch (Exception) { _mapTexture =

contentManager.Load<Texture2D>(_defaultFileName); }

_mapPixelColourData = new uint[_mapTexture.Width * _mapTexture.Height];

_mapTexture.GetData(_mapPixelColourData, 0, _mapPixelColourData.Length);

MapPixelCollisionData = LoadPixelCollisionData(_mapTexture, _mapPixelColourData);

if (isCollidable)

{

_collisionManager = CollisionManager.Instance;

_collisionManager.InitialiseMapData();

}

}

private bool[,] LoadPixelCollisionData(Texture2D texture, uint[] mapData)

{

if (mapData.Length != texture.Width * texture.Height)

throw new ArgumentException("MapData must match the texture data provided");

bool[,] boolArray = new bool[texture.Width, texture.Height];

for (int x = 0; x < texture.Width; ++x)

{

for (int y = 0; y < texture.Height; ++y)

{

if (mapData[x + y * texture.Width] != 0)

boolArray[x, y] = true;

}

}

return boolArray;

}

A reminder that a GameObject has collision points, which can reference their position with respect to this 2D bool array as x,y coordinates; each ‘point’ has a float for x and y, which are simply cast as integers ande indexed into the 2D bool array. For example a collision point is at position (423.2512, 120.8334), we check the value of MapPixelCollisionData[423,120] which is false, the pixel is empty and the point is not colliding with the map.

Updating the Data

Now that collisions are handled, it is simply a matter of calling the DeformLevel() method whenever there is an explosion which will change the map. For simplicity these are always circles, which we obtain by iterating through a square area of pixels. To keep things simple on the front end, the thing that is exploding only passes its centre position and the explosion radius. The Map method PositionInArray() calculates the relative position within the 2D bool array. I kept mathematical functions in a Utility class, this one is beautifully named “IsWithinCircleInSquare” which (obviously) checks if a point is within a circle drawn within a square. If it is, then set the corresponding value in the contiguous colour data array to 0, as it is now empty - and updating the bool array to false so that objects will no longer collide with that pixel. Then at the end of DeformLevel() we update the map Texture2D data so that it doesn’t show any colour at those points any more. And voila, desctructible, collidable terrain.

public void DeformLevel(int radius, Vector2 position)

{

int diameter = 2 * radius;

for (int x = 0; x < diameter; ++x)

{

for (int y = 0; y < diameter; ++y)

{

if (IsPointInBlastArea(radius, position, x, y))

{

_mapPixelColourData[

PositionInArray(radius, position, x, y)] = 0;

MapPixelCollisionData[

ArrayColumn(radius, position, x),

ArrayRow(radius, position, y)] = false;

}

}

}

_mapTexture.SetData(_mapPixelColourData);

}

private bool IsPointInBlastArea(int blastRadius, Vector2 blastPosition, int x, int y)

{

return Utility.IsWithinCircleInSquare(blastRadius, x, y) &&

blastPosition.X + x - blastRadius < MapPixelCollisionData.GetLength(0) - 1 &&

blastPosition.Y + y - blastRadius < MapPixelCollisionData.GetLength(1) - 1 &&

blastPosition.X + x - blastRadius >= 0 &&

blastPosition.Y + y - blastRadius >= 0;

}

//...Draw() method ommited for brevity.

private int PositionInArray(int radius, Vector2 position, int x, int y)

{

ArrayColumn(radius, position, x)

+ (ArrayRow(radius, position, y) * _mapTexture.Width);

}

private int ArrayColumn(int radius, Vector2 position, int x)

{

(int)position.X + x - radius;

}

private int ArrayRow(int radius, Vector2 position, int y)

{

(int)position.Y + y - radius;

}

}This simple but clever idea comes form this fantastic article. I simply changed things to suit my game. I tried to make the code as clean and simple as I could, which is not easy when iterating through multiple for loops.

MenuMenu Tools

Here I want to highlight some non-specific classes or tools I crated to build the menus in the game. I wanted a simple interface, so I chose to represent all settings graphically with integer steps.

The Wizard Grenade pause menu

Setting Class

The Setting class was developed to handle this, having both an integer property (e.g number of Wizards in a team), but with the option to calculate a float value if required; for example the “Music Volume” setting shown in the menu above will have a value of 2/5 = 0.4f.

public class Setting

{

public float Value { get; private set; }

public int IntValue { get; private set; }

public int MinValue { get; private set; }

public int MaxValue { get; private set; }

private SpriteMeter _spriteMeter;

public Setting(int initialValue, int minValue, int maxValue)

{

IntValue = initialValue;

MinValue = minValue;

MaxValue = maxValue;

Value = (float)IntValue / (float)MaxValue;

}

...

public void SetSpriteMeter(float maxWidth, float spriteScale)

{

_spriteMeter.Interval = maxWidth / (MaxValue - 1);

_spriteMeter.Sprite.SpriteScale = spriteScale;

}

public void SetValue(int value)

{

IntValue = value >= MaxValue

? MaxValue : value $lt= MinValue

? MinValue : value;

Value = (float)IntValue / (float)MaxValue;

}

public void ChangeValue(int diff) => SetValue(IntValue + diff);

...

}SpriteMeter Class

The SpriteMeter class simply prints a number of Sprite objects to the screen separated by an interval; the “SetSpriteMeter()” method in Setting can be used to calculate this interval. I chose to pass the value of the setting directly in the “Draw()” method.

public class SpriteMeter

{

public Sprite Sprite { get; set; }

public float Interval { get; set; } = 10f;

public SpriteMeter(ContentManager contentManager, string fileName)

{

Sprite = new Sprite(contentManager, fileName);

}

public void Draw(SpriteBatch spriteBatch, Vector2 position, int value)

{

for (int i = 0; i < value; i++)

Sprite.DrawSprite(spriteBatch,

new Vector2(position.X + (i * Interval), position.Y));

}

}Options Class

The Options class draws the text options out to the screen. The constructor takes a List of strings, and a ‘bool’ which determines a vertical or single position layout. The video clip right demonstrates the difference. I created another class called OptionArrows which will measure the length of the selected ‘string’ and adjust position. The Options class also handles changing option with the respective arrow keys (i.e. L/R for single, U/D for vertical) holding the List Index as an integer property.